The government has suspended the special open market sale of rice introduced to help the urban poor who were force to slash food consumption after being hit by the coronavirus crisis saying that they did not need help anymore.

‘We have stopped the special OMS programme because of the fact that the food crisis people found themselves in after the coronavirus struck is now over,’ director general of food Sarwar Mahmud told.

‘Bangladesh just reaped bumper rice harvest while their normal economic lives are gradually being restored since lockdown restrictions were lifted,’ he said.

Life is still hard but people have their means to cope with the coronavirus crisis on their own at the moment, said Sarwar.

The government decision to shut down special OMS shops, through which a limited number of ration card holders could buy a kilogram of rice at a subsidised price of Tk 10, comes amid depleting government rice stock due to poor procurement.

The decision surprised many, including the beneficiaries — the urban poor — and economists, as evidence grew that millions remained half-fed in Bangladesh as they tried to make up for the drastic fall in their income caused by the coronavirus crisis.

The situation is further worsened by a devastating flood that continued to wreak havoc across Bangladesh for over a month.

The United Nations recently said that Bangladesh needs to extend monthly temporary cash aid to 6.53 crore to the people so that they could bear their food, health and education expenses.

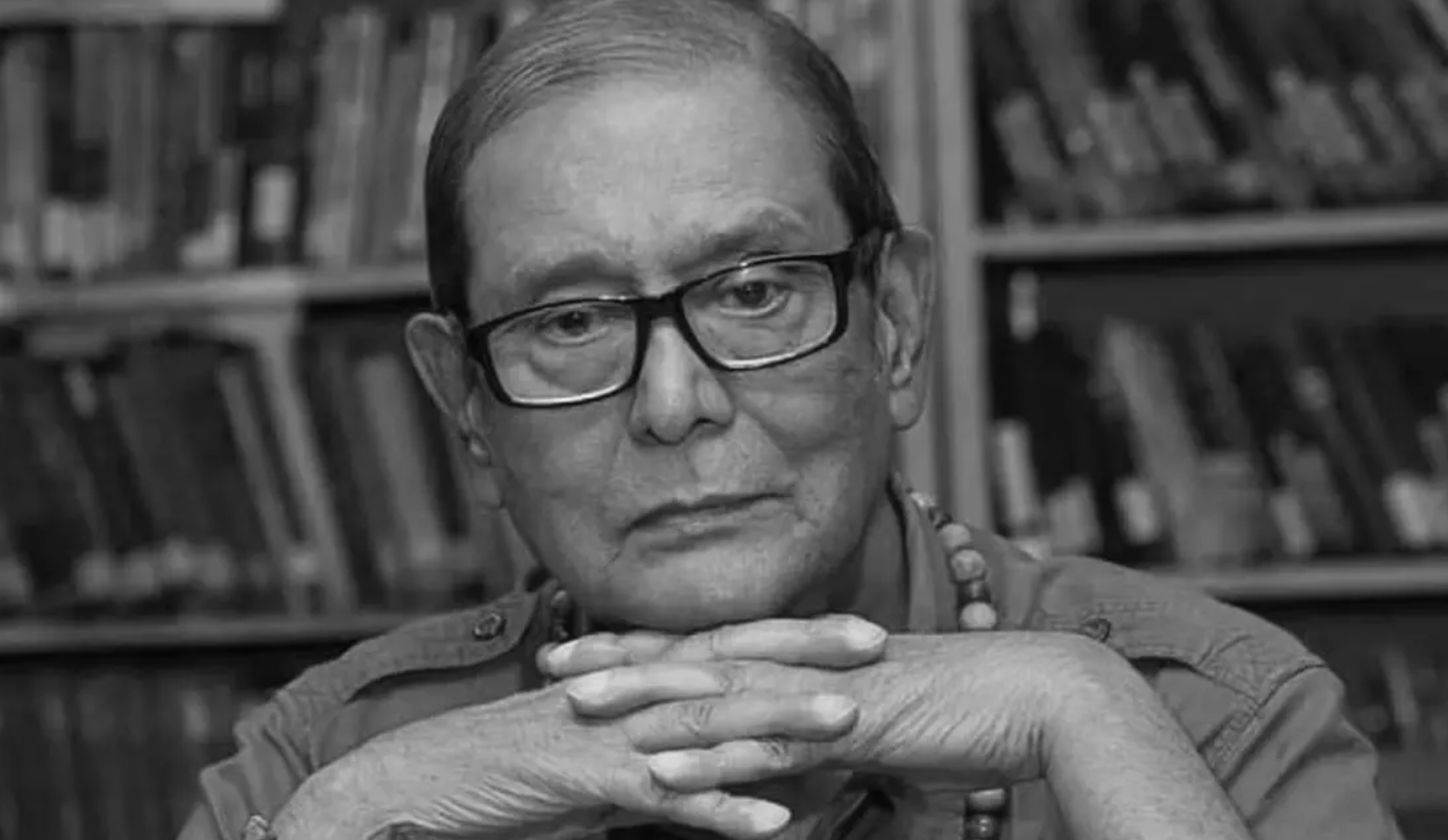

Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies professorial fellow Md Asaduzzaman said that the government misinterpreted the idea of urban poor as it sought to conceal its failure to help them.

‘Bumper rice production bears no implication on the urban poor for they do not grow rice,’ said Asaduzzaman.

He said that the government clearly failed to stock up enough rice needed to run the special OMS rice scheme and was making the poor pay for its failure.

‘It is a classic case of management failure when hungry people roam around, though there is no shortage of food in the country,’ said Asaduzzaman.

On July 25, the government rice stock fell to 12.85 lakh tonnes, half a million tonnes less compared to the stock on the corresponding day last year.

In April, more than two weeks after the coronavirus infection emerged in Bangladesh, prime minister Sheikh Hasina announced her intention of feeding the poor through the special OMS programme.

But the programme could not become fully operational until May because of the delay in the distribution of ration cards.

In May and June, the special OMS covered 33,02,600 people in cities and towns across Bangladesh.

Though in the first month the turnout of ration card holders was 86 per cent, it rose to 96 per cent in June, testifying to the growing need for food aid.

Nazrul Islam, founder and honorary chairman of the Centre for Urban Studies, said that the government must continue lending support to over one crore urban poor living in cities and towns.

‘They all are in emergency need of food and relief aids,’ said Nazrul.

Some of them might have returned to village homes as the coronavirus crisis broke out, but they would be back shortly because their livelihoods depend on cities, he said.

Different studies showed that the number of poor in the country grew after the emergence of the coronavirus crisis.

Last month, a study by Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies revealed that 1.64 crore people became newly poor because of the virus crisis.

On July 16, a Right to Food Bangladesh study covering 37 districts revealed that 87 per cent of the people surveyed were facing food crisis.

The study said that three-fourths of the surveyed people did not have any food in store and the rest could get by a week with what they had in stock.

The study included rickshaw pullers, hawkers, wage earners, small entrepreneurs, housemaids and drivers, 97 per cent of whom had their livelihood affected in a way or the other.

At least five per cent of the surveyed people ate once a day while nearly 42 per cent could not afford nutritious food, not even for children and lactating and pregnant mothers, said the study.

The directorate of food said that regular sale of OMS rice at Tk 30 continued as usual from July.

Per kilogram of coarse rice sold between Tk 38 and Tk 45 in the market until Monday after a 2.41 per cent increase in price over the last month.

‘We don’t mind eating less to save some money to pay the outstanding rent to the homeowner. We are simply helpless,’ said Dolna, 40, who was the proud member of a solvent family even in March.

Dolna’s son and daughter, who are garment workers, and her husband, a roadside vendor, lost their earnings over April and May.

Dolna and her family spent the month of July in their village home in Jamalpur in an attempt to settle down, but the flood forced them to come back to Dhaka.

‘We can use some help to tackle the crisis,’ said Dolna, who used to work as a housemaid but was denied employment by her previous employers upon her return.