Thousands of families had to give up their lands – in many cases, their ancestral property – for the Padma Multipurpose Bridge project and relocate elsewhere.

Years later, Tota Matbor, one of those many "resettled", now spends his days taking care of his crop on a leased piece of land. At night, he drives a battery-run rickshaw.

Now living in a resettlement site at Kumarbhog union in Munshiganj district, which covers 15.46 hectare land – somewhat larger than the Jamuna Future Park complex – Tota, a family man above all else, often recalls his prime days from six years ago as the owner of a thriving roadside restaurant.

"Hotel Matbor," as it was named, "was packed to its full capacity of 30 chairs, especially on Fridays," a beaming Tota told The Business Standard.

The Padma Bridge project acquired his old home by the River Padma in Munshiganj's Medinimandal union as well as the land of his business at the Mawa Chowrasta (crossroads).

Now, on his way to the Mawa market for groceries occasionally, Tota passes – with a heavy heart – a Padma Bridge project slab that stands in place of his once humble business restaurant.

Matbor lives in one of the better sites with lush green trees lining the entranceway off the Mawa highway. The residents live in rows of corrugated iron sheet houses or concrete houses with a few spruced up colourfully painted gates or mosaic tiled walls here and there.

And when they need to go anywhere, there are always auto vans, rickshaws or tuk-tuks whizzing in and out of the site.

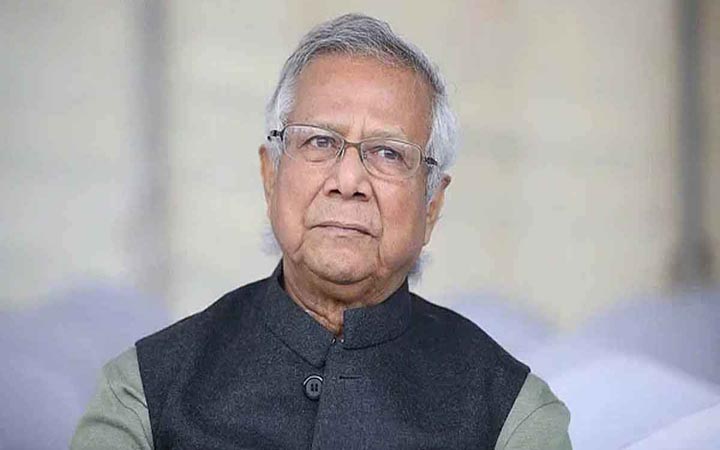

The 56-year-old Tota Matbor is a business enthusiast who has attempted to start a new business a couple of times ever since losing Hotel Matbor. "Regrettably, I failed. I even lost Tk6 lakh when I tried to start a restaurant business in the new ghat (Mawa terminal)," he added.

Tota is not the only one to have lost his business or changed profession due to the country's largest development project. The relocation, for most, resulted in a change in their livelihood.

More than 3,000 families have been resettled so far in seven sites across Munshiganj, Shariatpur and Madaripur districts, according to Khandakar Nazibul Hassan, assistant director (resettlement) of the Padma Bridge project.

For many of the 335 households on the site, the comfort of the paved roads and basic amenities – such as primary school, mosque, healthcare centre to name a few – do not quite make up for their old livelihoods.

Case in point is the farmers of Kumbarhog site.

It is not only a matter of income adjustment, the relocation also required a mental adjustment, the farmers claimed.

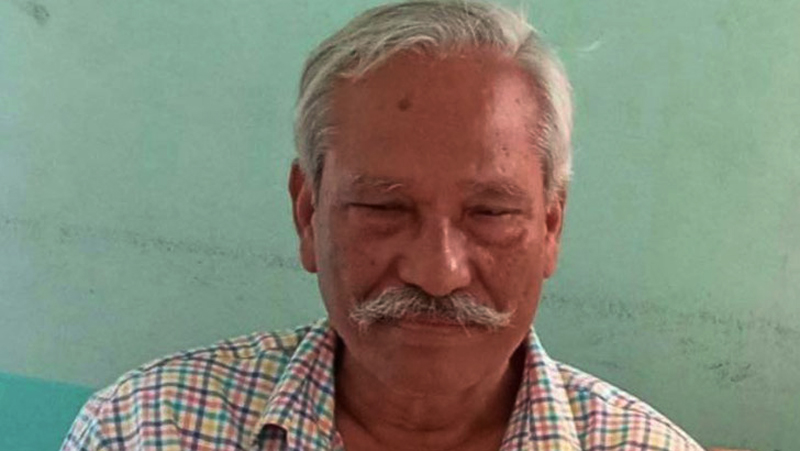

"Earlier, we could drink our cow's milk, planted vegetables around the house for the family, raised our own crops…probably the only thing we had to buy was fish," lamented Md Shahajan Bepari, one of the Kumarbhog farmers.

The salt and pepper haired, middle-aged farmer with an overactive eyebrow further explained the "pain" of having to buy every single thing along with something they never had to deal with, utility bills such as the monthly water bill of Tk400.

Livelihood morphed into a more laborious ordeal for those who continue to be farmers or work in agriculture after the relocation because they are not allowed to keep cows or poultry on the premises of the resettlement sites. They have to rent space offsite to continue their farming or agricultural work.

"These sites are like townships, it is difficult to maintain space for cow or poultry rearing," said Shamsul Haque Mridha, livelihood development specialist, Eco-Social Development Organisation (Esdo). "However, we would not deny permission to residents to rear cows on the site if they can guarantee a clean practice," Shamsul Haque told TBS.

Esdo, like Samahar Consultant, is one of the few NGOs that work in partnership with the government on a contractual basis to improve livelihoods of the site residents.

The farmers beg to differ.

Bare-bodied and soaked in sweat from the early April afternoon heat, with the hems of his faded lungi tucked in between his legs, Tajul Mollah lifted a hay basket on his head. "Farming is the only thing I know, how else am I to run my family if I do not rear cows?" said Tajul, a farmer and Kumbarhog site resident.

He was on the way to his rented cow shed – half a mile from his home. He needs to make at least two trips every day. That is walking roughly the distance from the Dhanmondi 32 bridge to the Farmgate foot over-bridge.

"We have the comfort of the paved roads here but not the nature we are accustomed to," Tajul added.

But not all resonate with his nostalgia and opaque dissatisfaction.

"If it was not for the resettlement, my house would have been long swept away due to erosion in the River Padma," said Abul Kashem Hawlader